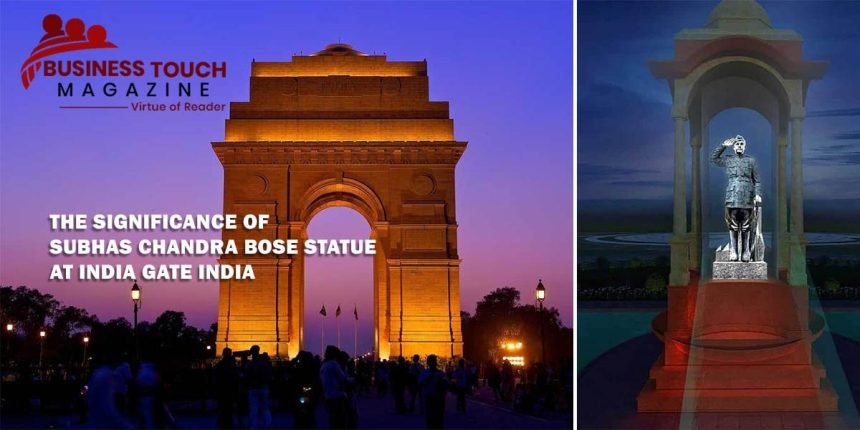

In conjunction with the renaming of Rajpath and Central Vista as Kartavya Path, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled a monument of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose made of 28-foot-tall black granite on Thursday. Until 1968, a statue of England’s King George V stood under the India Gate’s canopy, where the new monument now stands.

During his address, Modi added, “What heights would the nation be at now if after Independence India had followed the path of Subhas babu! Unfortunately, following the Declaration of Independence, we forgot about our nation’s greatest hero. His concepts, and the symbols that represented them, were disregarded.

Due to the efforts of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, as well as those of Subhas Chandra Bose in the 1940s, the old historical legacy of Kshatriya courage had begun to wane, and the monument represents this decline.

The presentation of Subhas Chandra Bose’s monument at India Gate and the inauguration of the Central Vista complex by Prime Minister Narendra Modi are historic events. Politicians charged with governing the nation will soon move into a new complex designed by an independent and flourishing India that is perfectly suited to their demands and the gravity of their concerns. Hopefully, its activities will reflect a newfound civility as well. While the new Central Vista complex as the nation’s majestic legislative complex is undoubtedly noteworthy, it is not this aspect that is genuinely significant. A monument of Subhas Chandra Bose decked up in his military uniform was recently unveiled at India Gate.

After waning under Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru despite the efforts of Subhas Chandra Bose in the 1940s, the monument represents a centuries-old historical legacy of Kshatriya courage that has been slowly restored after India’s self-inflicted military loss in 1962. In rejecting a history of appeasement and defeatism, Narendra Modi has provided a resounding reaffirmation of the India that is Bharat. He has revitalized a country by giving its people renewed focus and determination in the face of the hostile environment they now find themselves in. The symbolic alteration in India’s navy ensign is also an imaginative reaffirmation of India’s historical accomplishments and identity during the time of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. Of the numerous heroes of India’s freedom fight, Veer Savarkar would have approved of these developments.

In light of the above, maybe it would be useful to once again emphasize the political and historical context in which a rearmed Indian Army is both essential and justifiable. It would be particularly suitable to provide the choice of India’s inescapable destiny as a warring state. India is facing a historic moment of significant foreign military threats that have coupled with internal subversion, domestic power conflicts and outright separatism to harm it. Unfortunately, India is a complacent society whose indifference to the gravest of threats baffles. Yet, the country is very probably destined to suffer major assaults to its basic integrity as a sovereign entity. Within a decade, India will have grown into a far more difficult challenge for its regional foes and frenemies to deal with and eradicate as an obstacle to their own objectives.

For China, the sheer presence and economic might of India in the next decade will be the proverbial fly in the ointment, putting an end to China’s dreams of absolute control over the Indo-Pacific region. The economic might of India would make it no longer a possibly controllable competitor for Pakistan, with whom it could engage in jousting, parrying, and negotiating under the guise of formal equality. India will become an existential danger to it by virtue of Pakistan’s formation in the guise of an unviable artificial state to suit British geopolitical goals, as a militarised cantonment in India’s northwest. In particular, if Pakistan does not aggressively aid its rebellious regions, India’s success will serve as a hazardous separatist enticement.

Many Western countries have dreamed for a long time of regaining governmental control over India by converting it to Christianity and making it a submissive, subservient partner of the Anglosphere and Europe. The signs are clear to them, too. They properly believe India would clamp forcefully on the carte blanche evangelism was allowed by Jawaharlal Nehru and never actually curbed significantly by Indian administrations afterwards. In reaction to India’s adoption of relatively mild national measures intended to limit the influence of global evangelical forces, the latter have begun a campaign of defamation and subversion.

If India is to continue to exist as a nation and civilization, its leaders must arrive at a sober, realistic appraisal of the country’s current situation that is based on a firm understanding of the country’s historical context. If for no other reason, a community needs the rule of law and democracy so that its members may settle their inevitable differences via the court system in a civilized manner. The famous French philosopher Charles-Louis de Secondat Montesquieu believed that parliamentary administration and a division of powers may help reduce or eliminate the existential tendency toward Hobbesian conflict of “all against all” in human society. Adam Smith, a political philosopher and economist, contributed the great insight that individuals would be bound together by their need for each other as economic actors and to survive as a result of markets and the division of labour.

However, this idealized depiction of a possible solution to the Hobbesian dilemma is not representative of the complete historical experience. In the first place, having a constitutional parliamentary system does not guarantee that an orderly society would never collapse. For India specifically, the second and more basic issue is that constitutional and parliamentary governance are only put in place after societal unrest has subsided. A civil war’s winner may impose such a system of government, or the warring parties may call a ceasefire and try to work out their differences via negotiation. Even after Partition and the catastrophic mistakes of judgement made by Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s longstanding tensions and disputes were not addressed until a Constitution was imposed from on high. After establishing a level of internal social peace and stability, the polity must next figure out how to fit within an unstable international system characterized by traditionally predatory, hostile interactions between states. The Greek word for “man soldier” literally means “not for nothing.”

In this counterfactual view of international relations, war is always raging or tensions are always on the rise; periods of relative calm are the rare exception. However, many traditional descriptions portray the international domain as a functioning “society,” which implies attributing more to it than the constant enmity between its component members. There is nothing inaccurate about this depiction of a global society, given the many ways in which its member states have traded goods and ideas with one another.

While both peace and violence have always lived alongside one another, history continually shows that conflict is more prevalent. Conflict and preparation for war always end up victorious. A major factor in Germany’s final loss in World War I was the British success in blocking German food shipments. Fuel shortages were a major contributor to the Germans’ defeat on the eastern front, and nothing more needs to be said about the scope of economic warfare that followed military combat itself throughout WWII. NATO nations have just declared total war against Russia due to its invasion of the Ukraine. This military campaign involves a complete economic and trade embargo, as well as open propaganda war.