Bhavish Aggarwal, who started the largest ride-sharing company in India when he was just a young man, managed to keep Ola ahead of the more well-funded Uber.

The creator of Ola, Bhavish Aggarwal, saw a closed door that should have been left open during a recent visit to the Ola Futurefactory, which bills itself as the largest electric two-wheeler plant in the world. Witnesses said he quickly called the facility’s custodial manager and handed out a penalty that included three rounds of running across the several acre property.

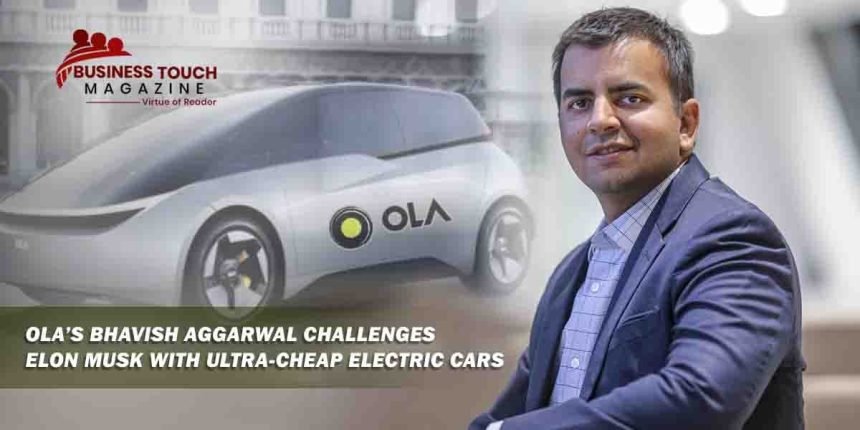

Mr. Aggarwal, 37, is one of India’s most ambitious businesspeople, but his unflinching approach has made him a contentious figure. The founder of India’s largest ride-sharing startup did it in his twenties, beating out Uber despite Uber’s much larger resources. Mr. Aggarwal hopes that his company, Ola Electric Mobility Pvt Ltd, may become the market leader for affordable electric vehicles and unseat Tesla Inc and BYD Co of China.

According to interviews with over two dozen current and former employees, who all requested anonymity for fear of retaliation, Mr. Aggarwal’s unrelenting pace and managerial style has irritated several managers and board members at Ola Electric, raising worries about safety and the business model.

Two-wheelers have been delayed due to supply chain issues. There has been a decline in sales. There have been reports of scooters catching fire, malfunctioning batteries, and dangerous software, leading to product recalls and apologies on social media platforms like Twitter. Mr. Aggarwal’s two multibillion dollar companies, Ola Electric and ANI Technologies Pvt, which manages Ola’s ride-hailing operations, have a higher turnover rate than average, with over three dozen key executives leaving within a year or two of arriving.

Mr. Aggarwal put ANI Technologies’s (at one point estimated at $7.5 billion, according to researcher CB Insights) initial public offering on hold late last year as internal issues increased and the global investment climate cooled. Several current and former executives of Ola Electric have indicated in interviews that the firm and its risk-taking founder are at a crossroads: Mr Aggarwal may become India’s equivalent to Elon Musk, or he could collapse under the weight of his own ambitious vision.

During an interview last month at Ola Electric’s luxurious offices in Bengaluru, Mr. Aggarwal remarked, “Passions and emotions run high and we are not on an easy trip.” He occasionally caressed the three office dogs, Happy, Husky, and Fatty. But I don’t want to pick the path that’s easier for me or Ola. That’s me in a nutshell: all of my fury and frustration.

The work Mr. Aggarwal is doing is interesting. There is no need for India to become the greatest market in the world for motorcycles because it is already the largest producer. With large investors and government money turning elsewhere, China’s achievement in producing reasonably priced automobiles may show poor countries how to phase out internal combustion engines and reduce pollution without resorting to prohibitively expensive electric vehicles. In India, electric vehicles are becoming competitively priced with or even cheaper than their internal combustion engine counterparts because to government subsidies and low labour costs.

Most people in the globe can’t afford even the cheapest Tesla, which, according to Mr. Aggarwal, starts at $50,000. With a range of possibilities between $1,000 and $50,000, “we have an opportunity to lead the EV revolution.”

Research and Markets estimates that by the end of the decade, India’s electric vehicle market will have grown to more than $150 billion, or about 400 times its current size. Mr. Aggarwal has been tweeting teasers of the company’s automobile design and a new battery innovation centre just a few months after Ola’s electric two-wheeler was released in December. He has worked tirelessly to disrupt the established Indian auto sector, which has been dominated by multinationals like Tata and Mahindra for decades.

According to Neha Singh, co-founder of Tracxn Technologies in Bengaluru, India, which keeps tabs on companies, “Bhavish Aggarwal strives for the world stage” by attempting to accomplish something monumental in the electric vehicle business. “Ola still has to cross a vast distance to make electric vehicles a mass market in India,” the author writes, despite the company’s early successes.

Mr. Aggarwal has stated his intention to create enterprises with long-term effects, regardless of the potential for annoyance it may cause. He argued that India can outperform its competitors in the EV market by investing in 5G infrastructure, renewable energy, and sustainable transportation. He argued that “the standard the world should assess us by” is how far forward we are in accomplishing our aims.

Sweat and tears, he maintained, were necessary for any truly significant achievement.